I Think We Can Fix College Basketball

Well, maybe not the bricked free throws, but at least the flow of the game

We just came off one of the best Final Fours in recent memory. So, why am I writing about how college basketball needs fixing? As good as the late-game drama was this past week, the product as a whole is still a bit stale, in my opinion.

I used to love college basketball growing up. As a kid, I won my dad’s office pool and earned myself a cool $100 after picking Duke over Arizona to win it all. I would often say the players care more and are more passionate than NBA players. They hit the floor, the fans were rowdy, and Dick Vitale was hyping you up from your couch.

But sometime between childhood and now, my tastes changed. I like watching pretty basketball with a sped-up tempo. I like seeing players make shots instead of brick them. And I like watching players who would be there for years instead of months.

Before the haters call me a hater, remember I used to be a huge college basketball fan. It was my favorite sport to watch. But that love slowly faded until I found myself only watching in March and early April.

While watching the tournament this year, I watched with a different lens. I saw the potential to get back the spark from my childhood. If only we could change a few things about the college game to make it more watchable.

When it comes down to it, I think there are a few issues:

The speed of the game is too slow

The game flow is too choppy

Players need to be empowered at the end of games

So here it is—my go at improving the college game.

The Speed of the Game is Too Slow

We have teams walking the ball up the court and passing around the perimeter for 28 seconds before throwing up an off-balanced shot. It’s just not that fun to watch. Teams run their sets without making any progress towards finding a good shot. In my opinion, the best way to speed up the game is by changing the shot clock to 24 seconds.

Reduce the Shot Clock to 24 Seconds

The purpose of reducing the shot clock to 24 seconds would be to 1) increase the number of possessions each team has, 2) increase scoring, and 3) improve the game's aesthetics.

A shorter shot clock would force teams to play quicker, increasing the game's intensity. Said Jamie Dixon of a proposed shot clock change:

"You have to get into your sets quicker. Be on the attack constantly. We don't want to be shooting in the last six seconds of the clock."

FIBA already uses a 24-second shot clock, which includes Team USA teams who compete before they are even in college. So it’s not like college players wouldn’t be able to adjust to a faster-paced game.

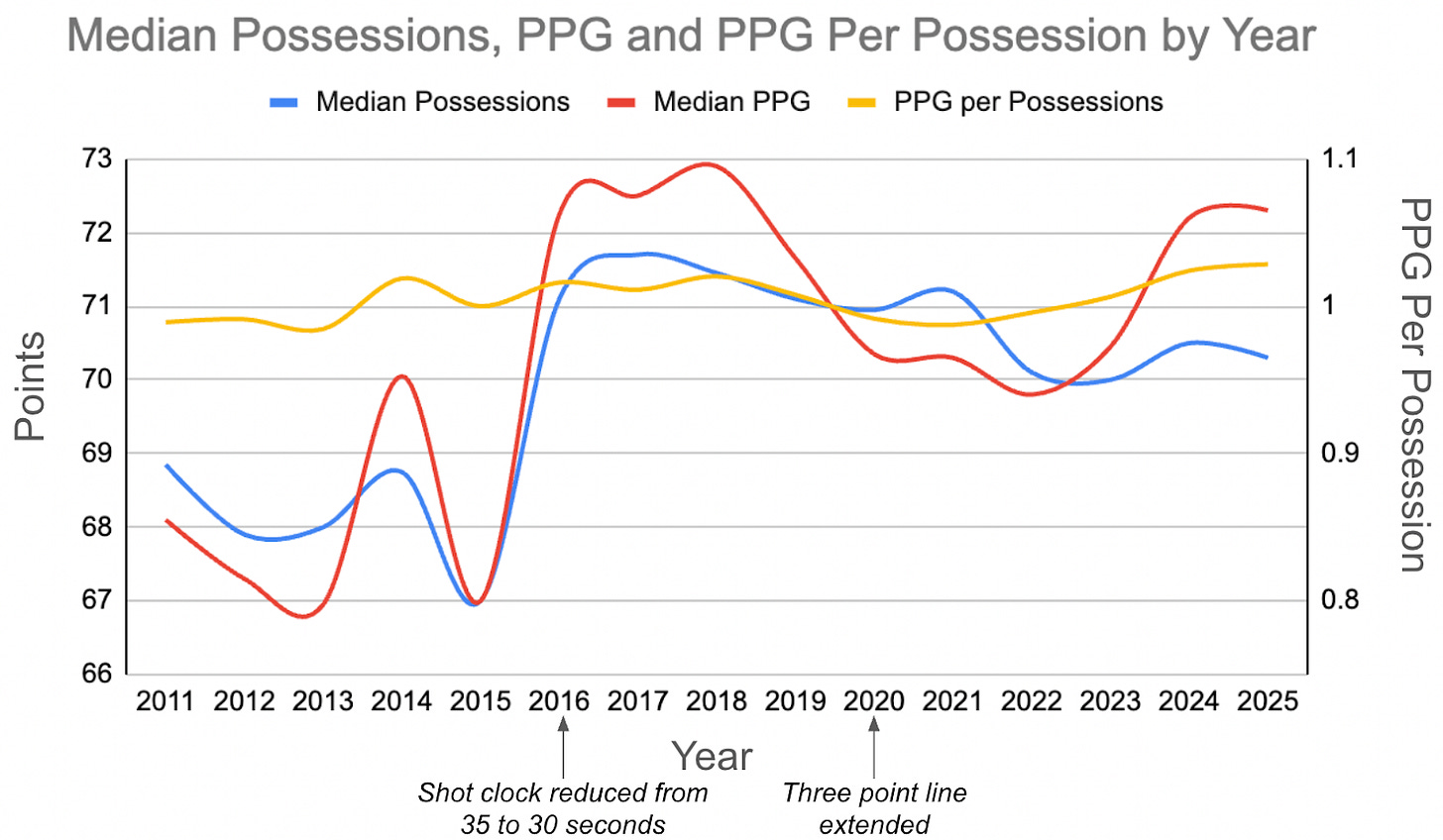

I decided to look at the potential implications of reducing the shot clock to 24 seconds. I looked back over the last 15 years and mapped out the median number of possessions, points, and points per possession on a per-game basis.

Over the last 15 years, a few rule changes impacted these statistics. For instance, the shot clock was changed from 35 seconds to 30 seconds in 2016, which resulted in an increase in possessions and points per game. Additionally, the extension of the three-point line was implemented in 2020, which resulted in a slight dip in ppg for a few years until shooters and offenses became adjusted.

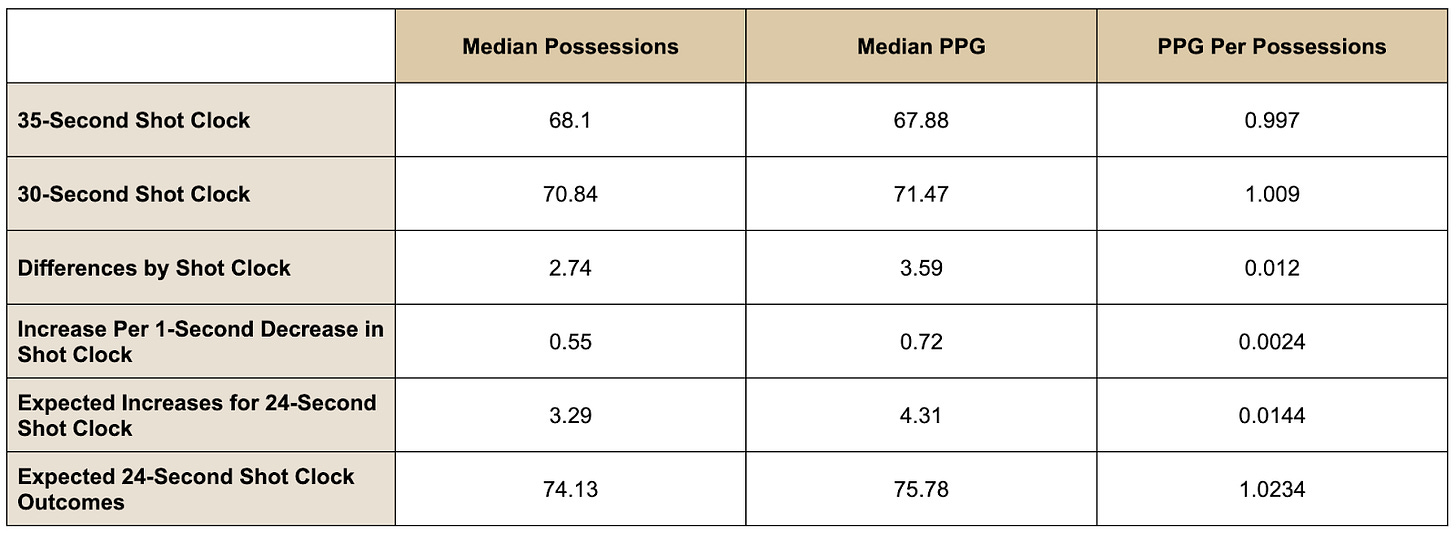

Looking at the difference between the 35-second shot clock era and the 30-second shot clock era, median possessions went up from 68.1 per game to 70.84 per game, a difference of 2.74 possessions. This also increased median points per game from 67.88 to 71.47, a difference of 3.59 points.

If we extrapolate on this, teams increase 0.55 possessions per one-second decrease in the shot clock. Additionally, every one-second decrease in the shot clock increases points by 0.72.

Assuming the same upward trend continues until the shot clock is reduced to 24 seconds, we will see a 3.29 increase in possessions and a 4.31 increase in points per game. This would bring the median possessions per game up to 74.13 and the median points per game to 75.78.

There may end up being an adjustment period as coaches implement new offenses and coaches get used to the new pace of the game. However, I would fully expect any adjustments to go smoothly given the same has been done in the above-mentioned shot clock and three-point line changes.

With that said, it is important to be aware of the potential downsides of changing the shot clock to 24 seconds. Teams with a lack of star power that rely on wearing down a defense late into the shot clock may have fewer opportunities to find cracks in the defense.

Critics of a 24-second shot clock in college have also said it could mean we have fewer upsets. With more possessions, there is an opportunity for more variance in the score between a team with NBA talent and a team without it. Adjacent to this argument is that fewer seconds on the clock will result in more isolation plays because coaches won’t be able to run as many offensive schemes, which would again, favor teams with talented players.

These outcomes are certainly possible. I believe the trend of fewer upsets is underway regardless due to the loosening of transfer rules and NIL. The best teams will accumulate the best talent, thus reducing upsets in March. And after watching this year’s Final Four, maybe that’s a good thing for the product on the court.

The Game Flow is Too Choppy

Too often college basketball games never develop a flow because of the constant stop-and-go nature of the game. Here are three ways to help college basketball find its rhythm.

Reduce the Number of Timeouts

In college basketball, each team is given four timeouts. In addition to team timeouts, there are timeouts every four minutes. These are known as the under 16:00 minute timeout, under 12:00 minute timeout, under 8:00 minute timeout, and under 4:00 minute timeout.

Assuming teams use all four timeouts throughout the game, 16 total timeouts will occur. In a 40-minute game, this comes out to a timeout every 2 minutes and 30 seconds.

In the NBA, each team is given seven timeouts. However, some of those timeouts are used for mandatory timeouts each quarter at the 6:59 mark and 2:59 mark if timeouts haven't been called previously. Teams can also only carry four timeouts into the fourth quarter and can only keep two timeouts with under three minutes left in the game.

The maximum number of timeouts that can be taken in an NBA game is 14, though sometimes these aren't all used. Assuming 14 timeouts are taken in a 48-minute game, there will be a timeout every 3 minutes and 25 seconds.

By reducing the number of timeouts in college basketball, the game will flow more freely, similar to an NBA game.

Don’t Allow Substitutions After A Second Made Free Throw (Unless a Timeout is Called)

This one is easy to implement and would reduce 20-30 seconds of teams standing around waiting to inbound the ball. Just force teams to make the substitutions after the first free throw and don’t allow the shooter to be substituted, just like the NBA.

Reduce the Number of Fouls Called

I looked at the number of foul calls per game in college vs the NBA. In college, the median number of fouls per game last season was 16.7 If you multiply that by two to account for two teams playing, it results in 33.4 fouls per 40-minute game. That comes out to be a foul call every 1 minute and 11 seconds of game time.

I followed a similar exercise for the NBA. The median fouls per team per game is 18.75. Multiplied by two teams is 37.5 fouls per game, which is about four more fouls per game than college. However, you must account for eight more minutes of play in the NBA. The result is a foul call every 1 minute and 16 seconds.

The difference isn’t huge—only a five-second difference between foul-call whistles. However, if you combine this over an entire game, plus all the timeouts, it results in the college game feeling much more herky-jerky than the NBA.

We know foul whistles happen more often in college basketball, but the question is why?

From the eye test, college reffing is much more inconsistent than the NBA. I watched multiple games this year where the refs allowed for a physical game in the first half, only to call a foul every time a player was touched in the second half (resulting in teams being in the bonus minutes into the second half). This makes it difficult for players to adjust to how the game is being called, which inevitably results in more foul calls. The gap in skill level between college and NBA refs is probably similar to the talent level of college and NBA players.

Another reason foul whistles may be more frequent in college is that teams start fouling to try and extend the game much sooner in college basketball than in the NBA. Many coaches are less confident in their team’s ability to get a stop and convert on the other end, so instead they will start fouling with 45 seconds left in the game.

Aside from less skill to compensate, coaches likely also do this because the shot clock is currently 30 seconds long. If you are down three with 36 seconds left, you are much more likely to foul than if the shot clock is 24 seconds. Coaches know that getting the ball back with six fewer seconds reduces their chances of tying the game.

Similarly, extending the game through fouling likely occurs earlier because teams can’t advance the ball on a timeout. They still have to throw the ball the length of the court in end-of-game situations. In the above example, getting the ball with six seconds left and having to dribble the length of the court is a lot more difficult than getting the ball in the frontcourt with six seconds left. And this brings me to my last rule change.

Players Need to be Empowered at End of Games

We should want rules that put the outcome of games in the players’ hands. The most obvious and easy rule change would be to improve end of game situations.

Advance the Ball on Timeouts at the End of Games

One of the most famous college basketball moments is when Christian Laettner hit a buzzer-beater after a full-court heave from Grant Hill. However, for every full-court pass that ends in a miracle finish, there are probably 100 others that end with the ball in the stands, bricking off the top of the backboard, or batted away by a defender.

In what should be the most dramatic part of the game, we often yawn because we know the outcome is inevitable 99.9% of the time.

Imagine if even five percent of those full-court chucks down the court were converted because they were switched to running a play from the hash. Being able to advance the ball and run a practiced ATO would add drama and excitement to the game.

According to BetMGM, 14% of NCAA tournament games between 2021-24 were decided by three points or less. Just think of all the shining moments we may have missed because teams have to go the length of the court at the end of games.

College Basketball Should Focus on a Better Product

The goal of these rule changes is to improve the overall product of college basketball. Yes, we’ll still have missed free throws and three-pointers that miss two feet to the right. However, the powers that be can’t control the skill level. Instead, the Rules Committee should focus on improving the game's aesthetics for a more enjoyable watching experience. After all, that’s how you will make and keep fans in a college basketball landscape where personnel changes overnight due to the ever-changing transfer and NIL rules.

The “Amateur” Sports Gold Rush

If you want to read more about NIL and the new transfer rules, check out this post. It goes through the impact of rules changes and how it's transforming the landscape of college basketball.

A agree 100% on all three suggestions. Especially the shot clock. Good thought process here....make it so number one.

Watch a Canadian university game. They have used the 24-second shot clock since 2007 and the game flows much better.