Take a gander into the intricate world of NBA roster building, where calculated moves, asset accumulation, and precise timing strategies come together to help teams transform into championship contenders.

A couple posts back, I mentioned competition is a feeling I often chase. Embracing competition is why losing can be so difficult. Most athletes will say they hate losing more than they enjoy winning.

However, in today’s NBA, half the league tries to lose at any given point during the season. The most public example is when the Mavericks were fined $750k two seasons ago for purposely losing to eliminate themselves from contention for a play-in spot to keep their lottery pick.

To be clear, players aren’t going out there trying to lose. It’s the leaders in an organization pulling the strings by sitting players. The NBA still hasn’t been able to align the incentives of winning now with building a winning team for the future. And that’s probably what makes it difficult for players.

Losing in the NBA

Players want to compete and win. No one likes going onto the court knowing they are just a filler to potentially get a higher draft pick and be replaced the next season. Players know they only have a few years to prove themselves, make money, and hopefully experience the chance to compete for a championship.

Most players are in the NBA because they are very good. And being very good means they were exceptional growing up, which translates to wins. Winning is what NBA players are used to. So when players arrive in the NBA to losing teams, it can be a culture shock.

After tying the NBA record of 28 straight losses, Cade Cunningham talked to reporters with a towel on his head. “I’ve never been through anything like this,” he said.

The Pain of Rebuilding

The answer for most organizations when winning isn’t happening is to rebuild. For a GM, rebuilding usually buys a few years of job security. But rebuilding can often be a long bumpy road, sometimes without any end.

My Portland Trail Blazers have recently entered a rebuild. They are officially in year two of their rebuild, but you could argue they are in year four after tanking at the end of the last two Dame Lillard seasons. As a fan, tanking is no fun. It’s difficult to stay engaged and excited.

I was watching a Blazers game the other night. Trailing by two with a few seconds left, my brother-in-law texted me saying, “Scoot 3 pointer (I want to lose lol).” If you know anything about Scoot Henderson's shooting, it’s that it's not great—he’s around 32% from three in his short career.

Looking around the league, a few other rebuilding teams include but are not limited to the Pistons, Wizards, Jazz, Nets, and Raptors.

The Pistons have been rebuilding on and off since 2009 with nothing to show except two playoff appearances and zero playoff wins.

The Wizards' current rebuild dates back to 2020 when they traded John Wall. For some reason, they delayed the inevitable and finally ripped the bandaid off last year when they traded Bradley Beal.

The Jazz have been in a rebuild since 2022 but were stuck in limbo the last two seasons since its roster was better than expected. They seem to be doing a good job of losing now, but we’ll see if the trend continues.

The Nets have been in a semi-rebuild since trading away Kevin Durant, Kyrie Irving, and James Harden in recent years. They thought they had a future with Mikal Bridges, but recently traded him to the Knicks, triggering a full-on tank for a top draft pick.

And finally, the Raptors moved OG Anunoby and Pascal Siakam after years of speculation to officially enter the Cooper Flagg sweepstakes.

In most cases, most teams should actively pursue a rebuild before committing to it. Many GMs and front offices try to enter a retooling phase to contend when they should probably tear it all down. When front offices aren’t definitive in their decision-making, rebuilds rarely work, and certainly not as quickly as they would like. This is a great article on what I would call, the anti-rebuild. Check it out for more details on what doesn’t work.

But when rebuilds do work, they are magic. The challenge for a GM is that there is no recipe for rebuilding. Rebuilding is an art form. One thing may work for one GM and result in a firing for another. However, as long as the incentives of winning now and building for the future aren’t aligned, there are some general rules of thumb when rebuilding an NBA team.

Collecting Assets

Let’s be clear, the art of rebuilding is much more applicable to small-market teams. Small market teams mostly have to build through the draft whereas big market teams can often rebuild by trading for and signing star free agents.

The key to rebuilding a small market team is to collect assets. Assets allow teams to take the time they need to build a roster that can win in the future. The easiest way to accumulate assets is by accumulating draft picks.

The more draft picks a team has, the more likely they are to turn those picks into future stars and role players. If teams have extra draft picks they don’t need, they can turn them into assets that can help them win when ready.

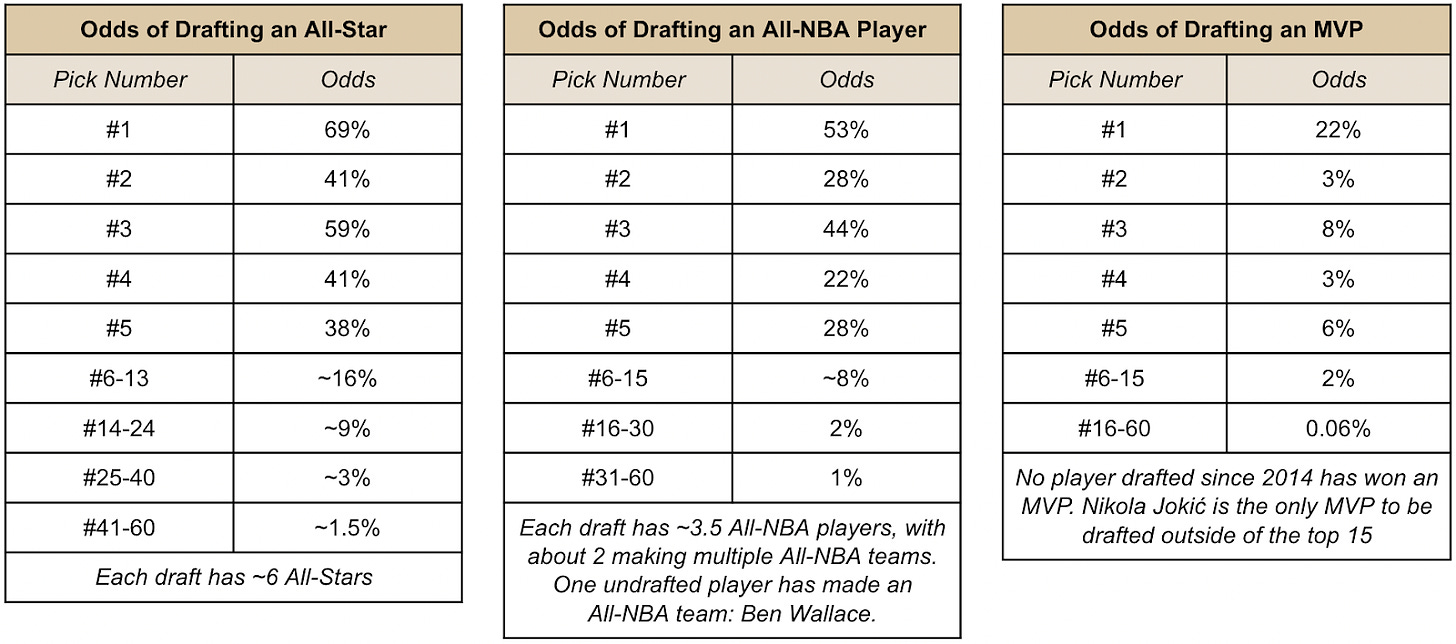

I turned to the data to understand how draft order impacts a team’s ability to select a star. Luckily, a Redditor already did a lot of the work for me, so here is the data since 1989:

Given the sample is small if you look at each pick individually throughout the years, you should ignore the differences between, say, the odds of drafting an All-Star at pick #2 vs pick #3. Instead, focus on:

Drafting higher in the draft yields better results

More importantly, having more draft picks improves the odds of drafting quality assets.

So, what are the most often used strategies to collect draft picks? Let’s dive in.

Trade Away Players With Immediate Value

Amid a rebuild, trading quality players who can add immediate value to a contending team is the best way to collect draft picks and ensure a losing record to increase the value of said draft picks. This is where most teams make the mistake of trying to re-tool instead of going all in on a rebuild.

GMs such as Sam Presti and Danny Ainge have recently shown how they are great at extracting draft picks for players who hold value.

When it was made clear Paul George wanted to go to LA, Sam Presti didn’t wait and took the Clippers’ best offer. Not only did they receive a future star in Shai Gilgeous-Alexander (which, at the time no one thought he would be as good as he is now), but they also received four unprotected first-round picks (one of which has become Jalen Williams), one protected first-round pick, and two first-round pick swaps.

Setting aside the Donovan Mitchell and Rudy Gobert trades, Ainge capitalized on a role player’s worth when he traded Royce O’Neal for a first-round pick. If you can remember, this resulted in the meme-able, “Why would they do that?” Brian Windhorst commentary.

As everyone else on the set tried to speculate why the Jazz would trade away an important piece of their team, Windhorst hinted at the fact that a rebuild was probably starting (Mitchell and Gobert would be traded soon after). Ainge made a trade and collected a first-round pick before it was widely known that the Jazz were entering a rebuild, which likely gave him more leverage in negotiations.

Take on Contracts others Don’t Want

If a team’s roster doesn’t have many valuable players who can add win shares to a contending team, the next best way to collect draft picks is to take on contracts others don’t want. This works because rebuilding teams don’t need to worry about making salaries work within the salary cap. Future assets (draft picks) are way more valuable than ensuring salary figures work in the short term.

One example is when Sam Presti and OKC (seeing a pattern here?) took on the salary of Al Horford from the 76ers after the experiment in Philadelphia failed miserably. As a reward for their efforts, they received a 2025 protected first-round pick.

Another example from Utah in 2013 was when they received Andris Biedrins, Richard Jefferson, and Brandon Rush from the Warriors. Golden State was desperate to dump $24 million in salary to sign and trade for Andre Iguodala. In exchange for helping the Warriors find the necessary cap space, the Jazz were rewarded with two unprotected first-round picks and three second-round picks.

Once teams have a treasure trove of draft picks, they can use them to build a winning team by either drafting or trading those picks for proven players. Hopefully, after a few years of building a competent team through the draft, teams will enter a post-draft-pick-accumulation era and start to see some win totals climb. That’s when the rebuild strategy switches from draft pick accumulation to salary cap optimization.

Building a winning team needs to be done within the salary cap limitations. To do this, teams need to make sure they have the cap space to pay stars or future stars and still have the necessary role players around them to compete for championships. This is hard to do in practice, but a few key strategies can be employed.

Match Player Timelines

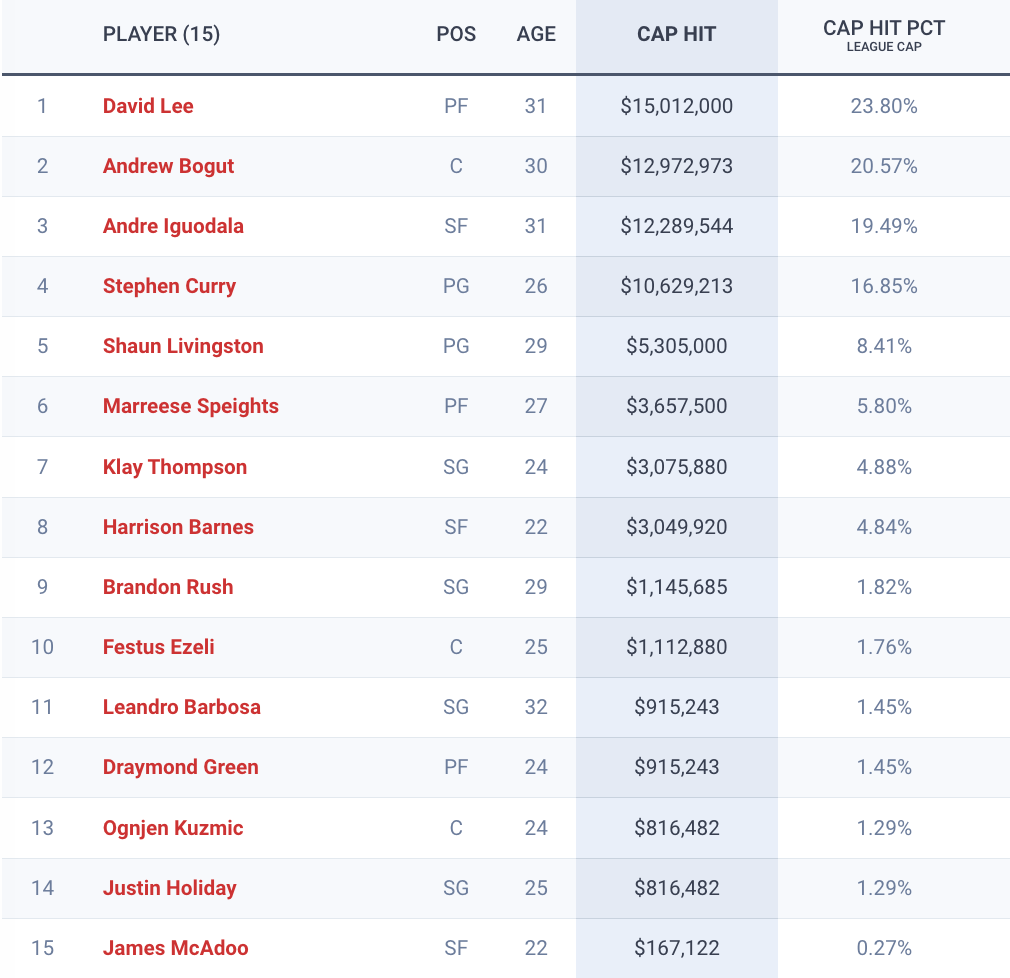

The Warriors dynasty is a great example of a team that was able to match player timelines to make it work given the salary cap restrictions. During their first championship run in 2014-15, the Warriors were technically over the salary cap, but still only had the 14th highest payroll in the NBA.

Even more impressive, Steph Curry only made a little over $10 million, Klay Thompson was just over $3 million, and Draymond Green was under $1 million. After drafting each of the three, the Warriors developed them and maintained them on team-friendly contracts. It worked because they drafted all three of them in a relatively short period. The timelines of their contracts all made sense before their salaries would blow out of proportion.

Like any good team though, the Warriors players had to be paid to retain them. And that’s what the Warriors did, resulting in the largest payroll in NBA history. However, the Warriors have an ownership group that was willing to spend and they were rewarded with four championships.

The challenge with building championship contenders is that so many ownership groups aren’t willing to spend like the Warriors, which is partly why player salary timing is so critical.

The Warriors have struggled the last two seasons as they’ve tried to rebuild an aging roster and have a two-timeline approach with Curry and Green on one end and their young talent on the other. The last two Warrior seasons have been a great case study on the challenges of building a roster with multiple timelines.

Take on Expiring Contracts

When teams are either ready to go all in on a roster, hoping to sign the missing piece through free agency, or need extra space to re-sign a rising star, taking on expiring contracts can be a strategy to employ.

The Knicks did this during their rebuild in 2019. They took on DeAndre Jordan's expiring contract from the Mavericks in the Kristaps Porzingis trade. New York did this knowing Jordan’s contract would come off the books in the summer, which allowed them to pursue (and fail) signing big free agents that summer.

In 2019, the Grizzlies were an up-and-coming team and decided to take on Iguodala’s expiring contract from the Warriors. Instead of just waiting until the offseason for Iguodala’s contract to come off the books, they were able to extract value by trading him at the deadline for a few players they valued more given where they were in their rebuild.

However, with this said, it will be interesting to see if taking on expiring contracts is still a viable option given the new collective bargaining agreement. The new rules make teams meet minimum cap thresholds sooner, which makes it more difficult to easily take on expiring contracts throughout the year.

Art + Luck

The strategies above are the art of rebuilding. Finding and keeping a star is a little bit of luck. It’s hard to predict which draft picks are going to pop and which are going to fall off into obscurity. It’s difficult to know if a star will want to stay in a single city long term. It’s challenging to know what injuries will derail a career. That’s why having as many shots on target as possible improves the odds of landing a star.

Winning is difficult in the NBA. Everything has to work in a team’s favor. But once a rebuild is complete, it’s time to compete. After all, competing at the highest level is why players play, GMs, build, and fans watch. A time to contend may only ever come once in the career of a player or GM, which makes going all in on winning a difficult decision. I wrote more about that here. Check it out.

One early takeaway from this article if I'm a player: I don't want to be the #2 pick! Save me for #3, please! (Haha)

Your article reflects the complexities of cap rules and collective bargaining, Austin. This is why clubs need their legal and accounting department right outside the GM's door.

And those on the set with Windy were totally lost by what he was saying. Which proves my point above....

Great post Austin! This was so insightful!