Sports and Parenthood

Rock climbing with my daughters

I grew up in a sporting family. My dad worked in sports the entire time I lived at home—he still does to an extent. I grew up going on sports trips with my dad and brothers to see our favorite athletes.

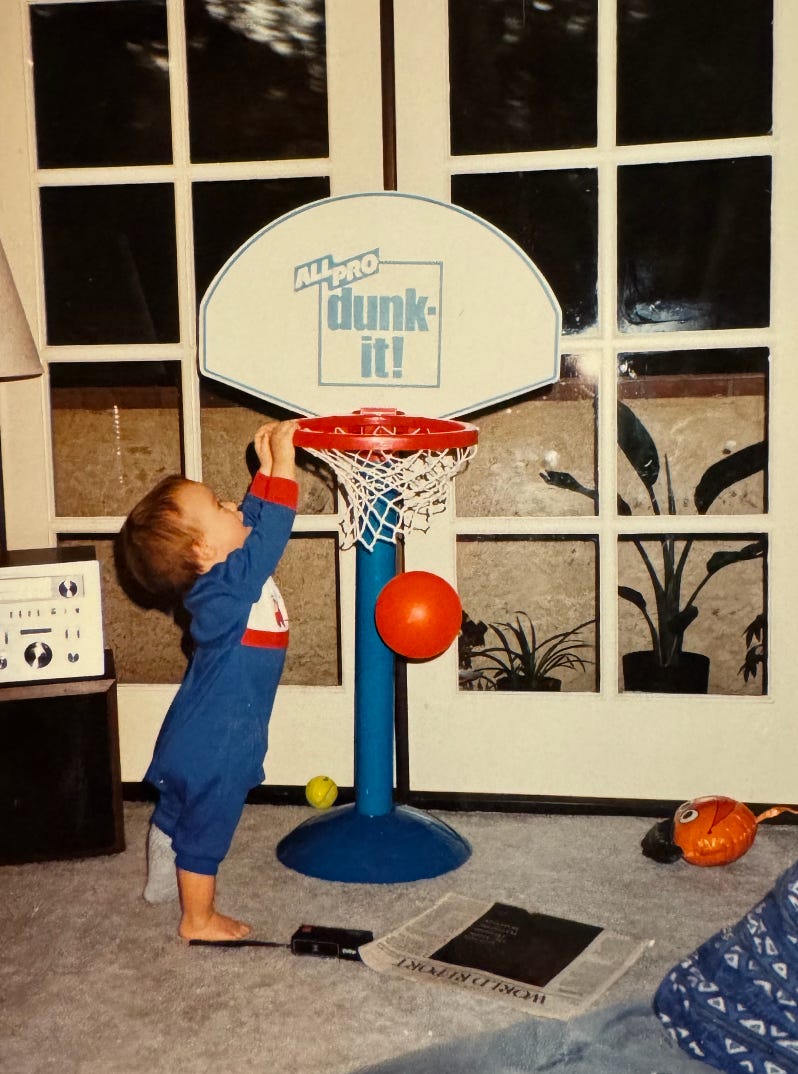

When I was a kid, I latched on pretty quickly to my favorite sports. My parents tell me I was shooting hoops before I was a year old. I also discovered soccer early on and grew to love it. Sports were a way to debate, celebrate, and spend quality time with my family.

Now I’m a dad and have my own family. Every sports-loving parent dreams of their kids being the next superstar athlete. My two oldest daughters, ages eight and five, have cycled through several sports. Soccer, gymnastics, dance, and cheerleading are the most prevalent. Some sports they are better at than others, but they haven’t really found the real love for sports that I had.

During the Olympics this past summer, we watched the women’s rock climbing events, cheering on the 23-year-old Brooke Raboutou as she took silver. Both of her parents were competitive climbers and now own a climbing gym in Boulder, Colorado, producing some of the best American climbers today.

My brother, who over the last few years has gotten into rock climbing, decided to build himself a climbing wall in his garage. My kids went over to his house and instantly climbed to the top of his 11-foot wall. My eight-year-old, who is timid in most aspects of her life, was scaling the wall and even jumping from one hold to another as she was suspended 10 feet in the air.

Climbing History

Climbing has always been a thing, but it became documented in the 1800s as a means to explore and summit peaks. Climbing was and still is a dangerous sport; however, in the 1930s, Fritz Wiessner introduced expansion bolts, which allowed climbers to anchor themselves to the rock face. This greatly improved the safety of climbing and opened up the path for climbing to gain popularity as a form of exercise and entertainment.

As climbing grew in popularity in the 60s and 70s, the sport began to resonate with hippie culture. Getting outside and becoming one with nature while also partying was attractive to hippies. The way hippies dressed and grew their hair was embraced by climbers. It was these climbers who lived together out of a van and rejected societal norms in favor of spending time in places such as Yosemite.

By the 80s, the emergence of climbing gyms started to appear. As the sport became more popular, the desire for easier access presented itself. The first climbing gym in the U.S. was built in Seattle, Washington in 1987.

Fast forward to today and the popularity of climbing gyms has grown exponentially. By the end of 2023, it’s been reported that there are 622 climbing gyms in the U.S. compared to 353 gyms in 2014. However, for comparison, for every 100 people who own a traditional gym membership, about one person has a membership to a climbing gym.

Though the number of climbing gyms is growing, there is still a lot of growth to be had. From a business perspective, the average revenue per gym in the U.S. is a little under $1 million. It sounds like a decent small business, but from a quick search on climbing gyms for sale, the cash flow is pretty small considering the high costs of running a gym (obviously, this could be somewhat biased since people may be selling gyms that aren’t as profitable).

Taking My Daughters to the Gym

A few weeks ago, I took my daughters to a climbing gym near my house. I hadn’t seen them that giddy since Christmas morning as they ran across the parking lot to get inside. Something just clicked for them. For my oldest, it was the complete opposite of what I had witnessed in soccer, where she couldn’t care less if she never touched the ball the whole game.

As we were at the climbing gym, my daughters wanted to try everything. For me, it was that connection with my daughters through sports that had been missing from the other sports they participated in. The connection comes because they love it and I’m helping them climb 50 feet into the sky without a care other than getting to the top.

As a parent, it’s hard not to get excited about something that your kids are excited about. It’s rewarding to see the joy they feel when they accomplish something—seeing them struggle on a portion of the wall and then come back and succeed later. It’s about them having fun and loving a sport that makes them happy. Their excitement may wear off, but for now they enjoy it.

What I’ve realized is that we’re all chasing feelings. For me, I think I chase four feelings—competition, love, spirituality, and nostalgia. Watching my girls climb checks the box of at least three of those feelings.

As they’ve gotten excited about climbing, I’ve been doing my part to try and understand as much about the sport as possible. Until this point in my life, I’d only ever climbed once or twice, so I have a lot of learning to do.

Types of Climbing

To me, one of the fascinating things about climbing is all the different styles and methods of climbing. The only thing I can compare it to in mainstream sports is the difference between playing tennis on clay vs grass vs a hard court.

The two types of climbing most are familiar with are bouldering and top rope climbing. These are the two types of climbing my daughters do as of now.

Bouldering is focused on climbing boulders instead of cliffs or mountains and is done without a rope. Most people don’t climb more than 20 feet in the air, so it is relatively safe if a climber falls.

Top rope climbing is often what you will see in a climbing gym. This is when a rope is anchored at the top of the climb, designed to catch a climber with someone belaying. This is slightly different from lead climbing, where a climber starts with the rope on the ground and clips into protection as they scale the wall.

The last climbing variation I’ll mention is called speed climbing, which is just how it sounds. Climbers will climb to the top of a wall as quickly as possible.

Competitive climbers usually compete in bouldering, lead, and speed climbing. In the Olympics this summer, bouldering and lead are a single event while speed is a separate event.

Climbing Legends

Though I have hardly any rock climbing knowledge, I have obviously seen Free Solo, the documentary on Alex Honnold’s free solo (climbing without ropes) ascent of El Capitan in Yosemite. I showed my girls the 10 minutes or so of the documentary when he climbed it. They were captivated and amazed at what he was able to do. When we went to the climbing gym the other day, my oldest said, “It would be cool if we saw Alex on the wall.”

I went hiking with a friend the other day and he said he believes Honnold’s climb of El Capitan is one of the most amazing human feats ever. I can’t disagree.

The average person, one who doesn’t have a climbing gym membership, probably hasn’t heard of any climbing legends other than Honnold. One reason is that climbing hasn’t yet hit the mainstream. Another reason may be because so many of the legends are no longer with us.

You see, the climbing legends are often legends because they do things that no one else has accomplished. Maybe this changes as climbing on artificial walls and Olympic coverage becomes more of a thing, but for now, the legends are made on real rock. And real rock is hard. It’s almost inevitable that a legend takes a nasty fall at some point. The question is whether they will be using a rope at the time.

One such legend, Mark-André Leclerc, was only 25 when he passed away in an avalanche accident. A Canadian Alpinist, he found his rush from soloing mountain peaks. However, unlike Honnold, he climbs on ice and snow.

In 2015, he became the first person to solo the 4,000-foot Corkscrew route on Cerro Torre in the Patagonia region of Argentina. A year later, he completed the first winter solo of the 8,800-foot Torre Egger in the same region. In the same year, Leclerc was the first to solo the 7,200-foot Infinite Patience route on the Emperor Face of Mount Robson in Canada.

One of the most remarkable parts of Leclerc’s climbs is that these routes require so many different climbing styles. He constantly has to switch between climbing shoes and snow crampons (the ones with the spikes) because of the different terrain. Like I said earlier, it’s like changing tennis playing surfaces every set.

However, even more unbelievable is that for him to consider his climbs a true solo, he would go without a phone or communication device. He felt that having such devices was a cop-out and a crutch. To add on top of all of this, he often performed on-site climbing, meaning he just showed up to the mountain with no dress rehearsal. He improvised along the way to make it to the top. This insane practice is shown in the documentary, The Alpinist.

To the average human, we look at something like free soloing and think, “extremely risky.” But Honnold thinks of it differently:

“I hate gambling. I hate games of chance. A lot of people when they talk about risk, it's like 'It's ok to fail.' Particularly with financial risk, people take financial risks because the upside outweighs the downside. But with free soloing, it's not like that because the downside is infinite, basically. I mean, death is a very big downside. I'm really making sure that that chance is a zero, you know?

A lot of people sort of conflate risk with the consequences. People look at free soloing, and they're, like, 'Oh, that's very risky.' But, the risk is the likelihood that something bad is actually going to happen. The consequences are what will actually happen if something bad occurs. So, with free soloing, the consequences are always really high, but sometimes the climbing is super-easy, so the risk is really, really low because there's basically no chance that you would fall off.”

Leclerc seemed to be on the extreme end of risk-taking, but even he was calculated in his approach:

“The most dangerous climb I ever did was when I soloed Cerro Torre when I was 21. After that, I sort of had a moment where I said, OK, that was a really cool climb, and I’m proud of it, and I think it made sense at that stage in my life, but I don’t think I want to expose myself again to that level of risk. I feel like that climb could be the high point of my life, actually, when you take into account the ratio of danger versus experience level.

I felt super intimidated, but right in the midst of the situation I had most feared, I just started to draw on all of the experience I’d been building, the systems and know-how in the mountains. I had purposely gone out and climbed by myself in bad weather—a lot—just to build experience. And in the end, it was fine.”

As I mentioned at the beginning, every sports-loving parent secretly wishes their kids to end up being a star athlete. I have to admit though, I may not want my kids to be too good at rock climbing. I’d worry every time they went to climb. I’m obviously getting ahead of myself, but who am I to hold them back if that’s what they want to do?

Right now, I’m just trying to embrace the quality time I have with them every week. Climbing is bringing us together in ways I haven’t been able to experience before and I’m all for it.

There must be something therapeutic about climbing. I've seen both of the author's daughters in moments of shyness or even fear of the seemingly harmless. But when it comes to climbing -- perhaps because no other person can interfere or affect their undertaking -- they are "free (to) solo".