Modern-day football (soccer) originated in England during the 1800s, with the first official game in 1863. With the unofficial “It’s coming home!” anthem, many English are proud that the world’s game originated on the fertile soils of their northern island. Expectations for England’s national team are always to win every major tournament they compete in, though they haven’t won one since 1966.

One major reason for that drought is because of a South American country known as the powerhouse of football. Little did they know that teaching a young schoolboy named Charles William Miller the game of football would create a monster. As Miller returned home to Brazil after completing his schooling in Southampton, he brought a football and introduced it to his mates. The rest is history.

I had the chance to go to a Copa América game between Brazil and Paraguay. I secured great seats between the corner flag and the goal. I couldn’t have asked for better luck, with four of the five goals happening right in front of us. Watching Vinicius Jr. carve up the Paraguayan defense and hearing the roar and chants of the pro-Brazilian crowd got me thinking about what makes Brazil so good at football.

Predicting Football Success

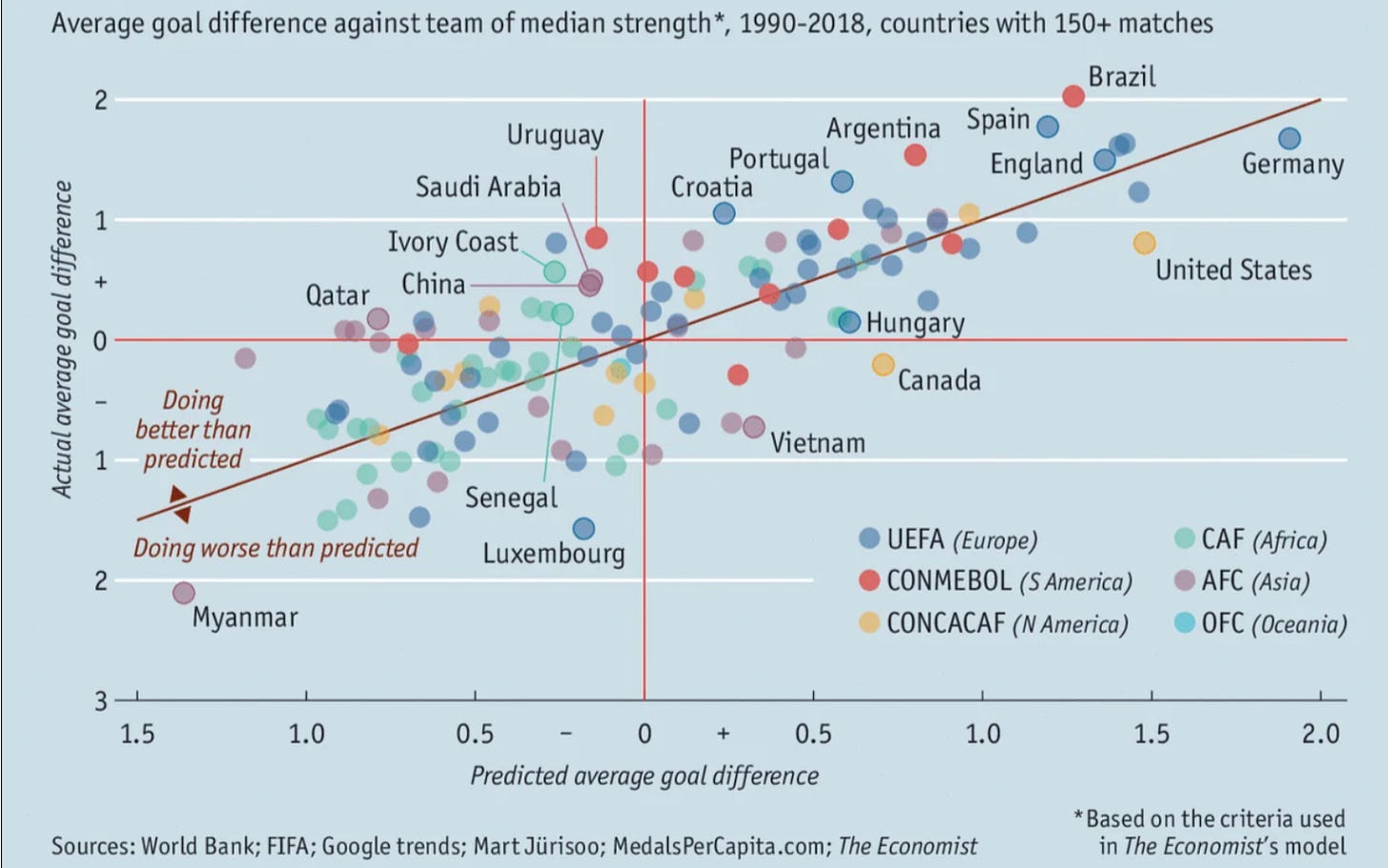

I recently listened to a book called Soccernomics, which broke down football success. The authors share that wealthy nations that have a long football history, access to football networks, and a large population pool tend to do better on the world stage.

More recently, The Economist conducted a similar analysis and found very similar findings, but also added that a nation’s interest in football played a big factor in footballing success.

Now, all of these factors seem intuitive enough. Wealthy nations will have more money to spend on player development, the sport’s infrastructure, and so on. A storied history and access to football networks enable improved coaching and innovative tactics. And a large population means more swings at the plate to field a competent team.

However, I want to focus on a nation’s interest in football because of so many of the qualitative factors that go into it. Interest can be observed in the culture and makeup of a country or neighborhood. It can be observed in the everyday behaviors of the up-and-coming generation. It can be seen in how laws are passed and holidays and events are celebrated. In essence, it’s what defines the social fabric of a nation. And that’s what football is to Brazil.

Brazil is Football

Carlos Alberto, the captain of the Brazilian team that won the World Cup in 1970, told the BBC:

“Football in Brazil is like a religion. This is the difference between Europe and Brazil. After the World Cup, people in Europe start to think about life, business. Here in Brazil, we breathe football 24 hours a day.”

Antony, a Brazilian playing for the storied Manchester United, said it best in The Players’ Tribune:

“The ball was my savior. My love from the cradle. We don’t care about toys for Christmas. Any ball that rolls is perfect to us...With a ball at my feet, I had no fear.”

In like manner, Adriano, a former Brazilian national team player, said:

“A ball was always at my foot. It was put there by God.”

In Brazil, everyone plays football—the kids, construction workers, drug dealers, and bus drivers. Dribbling a ball, everyone is equal, barefoot and all.

It’s not uncommon for a child’s first gift to be a football. Everyone dreams that their child will be the next Pelé or Ronaldo. During every major tournament, shopkeepers and business managers install TV sets in the workplace to dissuade employees from skipping work. Many businesses don’t even try and decide to shut down shop when Brazil plays.

At the epicenter of football in Brazil is futsal. With futsal courts about the same size as a basketball court, futsal can be played in crowded cities surrounded by apartment buildings. Futsal courts are bound to have cracks and potholes after years of wear and tear. With the uneven playing surface and small area, young Brazilian players learn how to dribble and play in tight spaces.

Pelé popularized the Portuguese phrase “Jogo Bonito,” meaning “the beautiful game.” Futsal is where much of the flair of the Brazilian game originated with stars such as Pelé, Zico, Ronaldinho, and Neymar, starting their careers playing futsal.

The style of the Brazilian game encapsulates Brazilian culture perfectly. Watching Brazilians play is like watching samba, with a tempo and energy about it that brings a smile to the faces of spectators. During the late 90s and early 2000s, Nike had several campaigns that characterized the type of football Brazil plays—none better than their commercial in 2006 for the World Cup.

The Roots of Brazilian Football

You can’t talk about Brazilian football without talking about the favelas. Favelas are the slums of Brazil, typically sprawling across the rolling hills on the outskirts of large cities. Often known for crime and danger, favelas are the lifeblood of Brazilian football.

Despite the economic growth of Brazil (the 11th largest economy in the world by GDP), the favelas are known for anything but economic prosperity. Though favelas have a thriving economy of their own, they are often built up informally and hacked together to make due. But that doesn’t stop some of the all-time greats from emerging out of the favelas.

Ronaldinho was born in a wooden hut and Pelé was born in a home made of salvaged brick. Rivaldo was so poor that he became bow-legged and lost his teeth due to malnutrition. Life in the favelas is anything but sunshine and roses.

The favelas can be a love-hate relationship for the people who live there. Douglas Luiz, a current Brazilian national team member, called it a community. It’s all he knows. It’s the favela alleyways that raised him.

Some players who play with local clubs still live in the favelas. In The Players’ Tribune, Antony recalled scoring a goal in 2019 against Corinthians in the Paulista Final. As he went back to his home in the favela, people pointed at him, yelling, “I just saw you on TV!”

The favelas can also be a living hell. Literally. Antony came from a favela in São Paulo nicknamed Inferninho, which translates to “little hell.” Antony has written about the drug deals that happened outside his childhood window and the fact that guns aren’t scary to him—that they are just a part of everyday life.

He shared a story of walking to school when he was eight or nine and approaching a man lying in the alley, only to realize he was dead when he got closer. The only thing he could do was jump over the body and keep walking to school.

All young kids in the favelas have a dream of getting out and putting on the iconic yellow Brazilian jersey to represent their country. The poverty of the favelas can actually be used as a benefit to become a professional footballer. Instead of playing an Xbox, which most families can’t afford, kids play football in the streets all day long.

In the favelas, there are informal networks and systems to discover new talent. Scouts and agents will literally watch kids playing in the streets and pick one out to join the neighborhood futsal team, or if they're lucky, the youth academy of a local football club. The academy systems at Brazilian clubs are well-developed. They are incentivized to develop young talent to sell for millions of dollars to the richest European clubs.

It’s not uncommon to be playing with your neighborhood friends one day and be flown to Europe the next. Adriano was asleep in his favela home when it was announced on TV that he was being called up to the national team at 18 years old. His family had to wake him up to tell him the news. The next year he was in Italy playing for Inter Milan. Similarly, Antony went from living in the favelas to Ajax to Manchester United in just three short years.

Many Brazilian footballers who were raised in favelas say that their only goal as kids was to get their family out. Antony credits the favelas for his success. Football isn’t scary for him because of where he came from. He writes the word “FAVELA” on his boots to remind him of his upbringing and to help relieve some of the pressure he may feel on the field.

Winning is Everything

Tim Vickery, a South American football journalist, quoted a Brazilian colleague saying:

“Our national sport isn’t football; our national sport is applauding the winners.”

Brazil fans haven’t been able to applaud their national team much these days. They just crashed out of the Copa América, losing to Uruguay in the quarterfinals. Danilo, a current national team member, recently wrote a letter to Brazilian fans apologizing for their lack of success. Perhaps the low point for Brazil came in the 2014 World Cup semifinals when they lost to Germany 7-1 on their home soil.

Many have blamed the lack of success on Brazilian players playing their club football in Europe and having to suppress their flair and creativity to adjust to the rigid systems of play (many blame Pep Guardiola’s tactics spreading like wildfire, which I wrote about recently). Some say there have just been a couple of generations where the talent level hasn’t been as good as in the past. Others blame corruption happening among Brazilian players and the football federation.

Yet despite Brazil’s lack of recent success, they are still the gold standard for footballing nations. Brazil is the pulse of the football world. The asphalt of the favelas and the crowd around the storekeeper’s TV can be felt in the rhythm of the Brazilian game for all to feel. Brazil is still the biggest exporter of football talent to the best leagues in the world. As long as Brazil’s interest in and passion for the game continue to thrive among its youth, the national team will be in good hands.

Is it time for Butterflies to explore why the U.S. still has not cracked the code of soccer success? We've been promoting the game for 50+ years, but have little to show for it.